DANIEL CHESTER FRENCH

“Having the opportunity to research the life and work of Daniel Chester French has been much like occupying a privileged front-row seat inside his gorgeous Chesterwood studio—observing the artist at the very site where a brilliant perfectionist conceived, molded, and marketed the monumental art that would represent America’s highest aspirations. Although French directed his unique creativity exclusively through his sculpture, I am beginning to form a new and more complex portrait of the private man and public tastemaker based on his correspondence, memoranda, and rare but revealing interviews. I have rarely encountered such a dedicated professional. ”

—Harold Holzer, Lincoln scholar and author of biography of Daniel Chester French, Hudson, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 2019.

It is no wonder that Daniel Chester French sought respite from the noise and frenzy of New York City and created Chesterwood, his retreat in the Berkshires. French was rooted firmly in the traditions of New England, with ancestors who sailed from England in 1630, landing in Ipswich, Massachusetts. Nine generations later, on April 20, 1850, Daniel was born to Judge Henry Flagg French and Anne Richardson French in Exeter, New Hampshire. Christened Daniel, the boy later added the middle name of Chester in honor of the New Hampshire town where his grandfather lived.

At his father’s urging, French entered the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1867. Science, however, was not his forte—he failed chemistry, algebra, and physics and was back at work on the family farm the following summer. French’s career began in an almost offhand way with the help of May Alcott (1840–1879), the sister of Louisa May Alcott and the model for Amy in Little Women. French recounted:

I had been whittling and carving things from wood and gypsum, and even from turnips, as many boys do, and as usual, ‘the family’ thought the product remarkable. My father spoke about them to Miss Alcott, as the artist of the community, and she, with her ever ready enthusiasm, immediately offered to give me modeling clay and tools. I lost no time…in experimenting with the seductive material, although I didn’t even know how to moisten it. [1]

The sculptor’s early work consisted of portrait busts and reliefs of family and neighbors, as well as a series of immensely popular figurines that accrued some royalties to put toward the cost of French's art education. In 1870, French undertook a measure of formal study. He spent one month in New York City at the studio of sculptor John Quincy Adams Ward (1830–1910). In the winters of 1870–72, he studied anatomy in Boston with physician and sculptor William Rimmer (1816-1879).

In November 1873, the town of Concord, Massachusetts, commissioned the 23-year-old French to execute a statue commemorating the centennial of the Battle of Concord in the Revolutionary War. Unveiled in 1875, the bronze Minute Man was an immediate popular and critical success.

French, however, missed the festivities of the unveiling. Like many artists of his generation, he was interested in studying art abroad. He received an invitation from Preston Powers, son of the distinguished neoclassical sculptor Hiram Powers (1805-1873), to live in Italy. French lived in Florence, Italy from 1874 to 1876, and studied and worked in the studio of the expatriate American sculptor Thomas Ball (1819–1911).

Having planned for seven years to undertake further study to augment his limited formal training, French returned to Europe in 1886 and traveled to Paris. There, he studied drawing with Paul Leon Glaize and investigated the techniques of modeling. His other teachers at the atelier included such sculptors as Emmanuel Frémiet, Paul Dubois, Jean Falguière, August Bartholdi, and Marius Jean Antonin Mercié. This was his first real exposure to Beaux Arts, a genre of increasing importance in America due to the influence of French’s friend and fellow sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907). The experience significantly shaped his later work.

1888 was a watershed year for French. He returned from France and married his first cousin Mary Adams French (1859–1939) in Washington, D.C. The young couple moved to New York City and the artist worked in a studio at the back of their brownstone townhouse. French’s reputation as a sculptor continued to grow and French won a medal from the Societé National des Beaux-Arts, only the second in the history of the Societé to be awarded to an American. As preparations progressed for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, the advisor for sculpture at the Exposition, asked French to execute six works, a significant contribution to what would be a groundbreaking World’s Fair in many ways.

At the peak of his career, in 1896, French purchased an old farmstead in the Berkshire Hills of western Massachusetts where he established a summer studio, home and formal gardens, naming the property Chesterwood. For the next 35 years, the French family would reside in the Berkshires from May through October, where they enjoyed entertaining friends in his studio.

The first decade of the 20th century found French at work on three major commissions: the Alma Mater, the Continents, and the Melvin Memorial, all among the most ambitious and successful examples of American architectural sculpture ever executed. Several years later, in 1915, French executed Mourning Victory, the centerpiece of the Melvin Memorial, which was commissioned in marble.

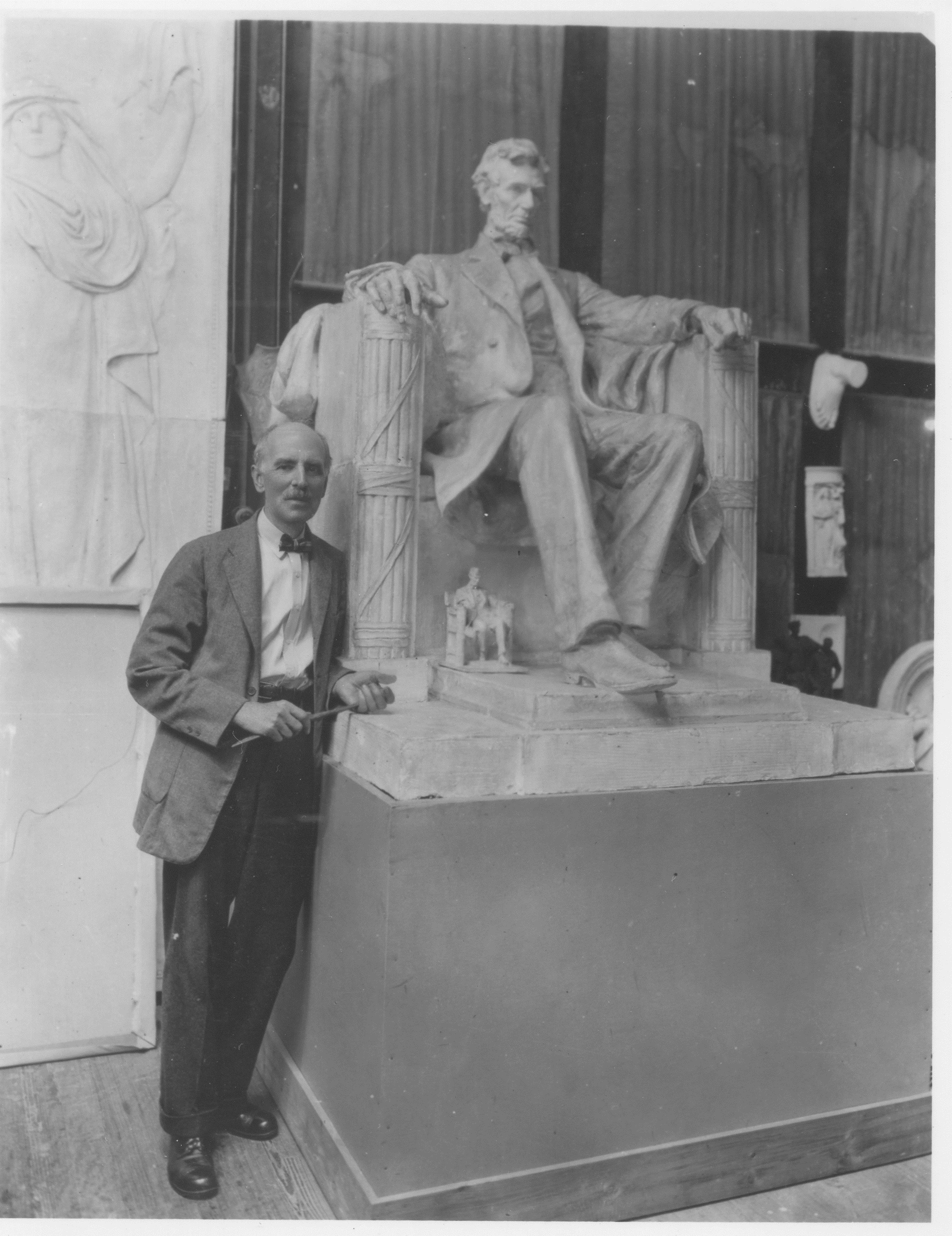

French most likely became acquainted with architect Henry Bacon (1866–1924) in Chicago in 1893 where Bacon was working for the architectural firm McKim, Mead and White at the World’s Columbian Exposition that year. In 1914, as part of a large rehabilitation of the Mall in Washington, D.C., the Lincoln Memorial Commission selected French to create a statue of Abraham Lincoln for the Memorial that Henry Bacon had been commissioned to design. Dedicated in 1922, the monument would become their greatest joint effort—a project of eight years resulting in a significant national shrine with international meaning.

Daniel Chester French was recognized for his pre-eminence as a sculptor during his own lifetime. As one of the founding trustees of the American Academy in Rome and a trustee of The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, French was highly esteemed among the established artistic community of his day and received honorary degrees from Harvard, Yale and Columbia Universities. The Academy of St. Luke in Rome, the Fine Arts Class of the French Academy in Paris, and the National Academy of Design (in New York) all elected French to their membership. In addition, he was a director of the Corporation of Yaddo[2] the artist colony. Presidents Roosevelt and Taft both consulted with French regularly on matters relating to aesthetics and art.

At his artistic maturity, Daniel Chester French was an outstanding architectural and public sculptor in the United States. After Saint-Gaudens’s death in 1907, he became the foremost sculptor in America working in the classical tradition—a position relinquished only at his death. On October 7, 1931, French suffered a heart attack and died at his beloved Chesterwood, a place of art and beauty, surrounded by the beautiful results of his lifetime of creative genius, created for his own inspiration as well as others.

[1] DCF, (June 14, 1926), Prelude to May Alcott: A Memoir by Caroline Ticknor (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1928), p. xx.

[2] Since 1926, Yaddo has been a colony for artists and writers in Saratoga Springs, New York. The estate was originally the home of New York stockbroker Spencer Trask. Daniel Chester French, along with Henry Bacon, created a memorial to Trask entitled Spirit of Life (1913–15; bronze), which is in Saratoga Springs.